Writing in the pages of New Statesman, democracy campaigner and all round good-egg Anthony Barnett has asked its readers ‘what about my country?’. Barnett speaks as an Englishman who wants to challenge the English-born liberal or progressive readers of the New Statesman who ‘almost certainly don’t “feel English”‘? This inability to identify with their own nation, despite appearing English (including to our immediate neighbours Scotland and Wales) is, according to Barnett, a form of English nationalism born from centuries of imperial primacy which ‘have produced a fused identity: British on the outside and English within’.

when someone born or bred in England tells you – or perhaps when you yourself say – “I don’t feel English”, it is not just a claim to uniqueness, it is English nationalism.

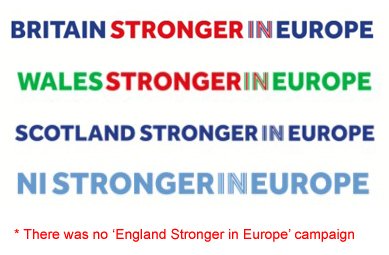

What Barnett speaks of is the national exceptionalism of the Anglo-Brit, exemplified by the Remain campaign’s inability to appeal to a discrete sense of English identity, despite recognising the political importance of the identities of the other nations of the UK. It’s unlikely that this was a strategic decision; it is probable that it never even occurred to them to address the English due to their inherent sense of uniqueness.

To the Anglo-Brit, Englishness is a cultural thing (sport, landscape, art) rather than a political thing. Unlike lesser nations, we have no need of nationalism or even political representation as England and the English. We are unique. Anyone who disagrees and advocates for England to be treated as a normal country with its own parliament, government and first minister is dismissed as beyond the pale, an English nationalist or ‘Little Englander’. The imperial British identity is sufficient for the first among equals in our Union of Equals.

Who do we call when we want to call Europe?, asks Barnett, before answering his own question.

Today, the answer to that question is Ursula von der Leyen. But what about my country? There is an English health service costing many billions; there is English Heritage, regulating our historic sites and buildings; our education system is English. “Have you ever wondered why no politician talks about rebuilding England?” asks the English Commonwealth website. “Why, when their housebuilding policies apply only to England, is it framed as ‘Rebuilding Britain’?… How is a pledge to build 1.5 million new homes in England the answer to Britain’s housing crisis?”

So? What about England? Who does speak for England and who do you call if you want to call England? The Anglo-Brit would say ‘Keir Starmer’ because for them Britain is Big not (Little) England, Great Britain not (provincial) England. England is, in the words of Barnett, ‘sidelined thanks to the “greatness” of being British’.

The day after Barnett’s article was published, Keir Starmer set out six milestones for ‘our country’. Two of those milestones were relevant to the whole UK, one concerned England & Wales, while three were about England-only policy areas. Yet Starmer went to great pains to avoid mentioning England.

Hilariously his social media team contradicted him. While he talked of Britain they said England.

Starmer is one of those who, like the readers of New Statesman, doesn’t “feel English”, at least not in a political sense. His ‘Plan for Change’ is British, a vision for Britain articulated in the language of Britishness even though it is primarily about England. The policy levers are English but the imagined nation is Britain. England is at once occluded by Britain and at the same time the imperial centre and driving force of the Anglo-British state. Those who don’t “feel English” benefit from this arrangement to the detriment of those of us who do feel English, and who feel unrepresented and would like English identity to be normalised.